County cricket has had a long innings - is it nearly over?

Words - Tom Chambers

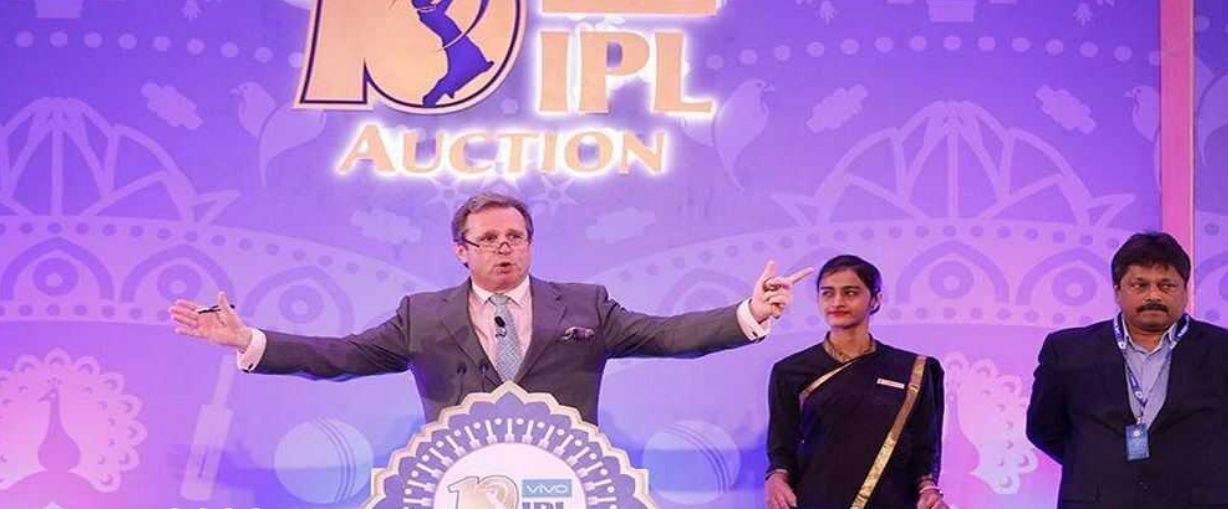

After nine frantic hours spent haggling and bartering, the eight franchise owners of the new Indian Premier League (IPL) emerged from their basement den and out into the sticky heat of a Mumbai evening.

The police were there to meet them, shielding the entrepreneurs and Bollywood stars from the camera lenses and microphones of the world’s media before guiding them to their waiting cars. Just behind the barriers, a baying crowd jostled to catch a glimpse of the men who had just made their city the centre of the cricketing universe.

The Mumbai Hilton Towers Hotel is an unlikely location for a revolution, but between the hours of 11am and 8pm on the 20th February 2008, the IPL’s dealbreakers and rainmakers caused a seismic shift in the foundation of the sport.

An accumulated $42 million was spent on cricketing talent - a figure previously unheard of in the game - that made star cricketers and journeymen alike richer than they had realistically hoped to be.

IPL2020Live - 18saurabh

IPL2020Live - 18saurabh

Meanwhile, 5,500 miles away, Worcestershire’s head groundsman Tim Packwood was busy at work preparing the county’s 112-year-old ground for another summer of English county cricket. It had been a difficult winter in the West Midlands, where seasonal rains had repeatedly caused the nearby River Severn to burst its banks and flood the outfield.

The team’s chief executive Mark Newton lamented the damage that the floods had caused to both the county’s playing surface and its delicate finances in an interview with The Guardian’s David Hopps.

"The most horrific moment was not the first flood in June [2007]", said Newton, "although that was bad enough. It was when, after all our work, with 200 volunteers cleaning and Lancashire here for a championship match, it happened again."

"I could bore you to death about flooding", Newton continued. "I have diagrams of every river and stream that flows into our catchment area. I have bar charts of every flood from the 1950s. I can't stop watching weather forecasts. But we have not lost our homes like some people around here. We just have to get on with it."

The total bill for repair work to the flood-damaged cricket ground was over £1.1 million – a crippling amount for a county hoping to make a modest £50,000 profit for the year.

The ECB's latest set of published accounts show it has just £2 million left in cash reserves, down from £68 million pre-pandemic.

Unlike the newly established IPL, English cricket is not, and has never been, an institution saturated with investment from wealthy backers (the ECB’s latest set of published accounts show it has just £2 million left in cash reserves, down from £68 million pre-pandemic).

In fact, until recent years, the English game has often looked sneeringly at the profiteering methods adopted by other sports and leagues. To this day, many within the game still associate English cricket with its 19th and 20th Century heyday of ‘gentlemanly conduct’, village greens, and breaks for tea on hazy summer afternoons.

Worcestershire’s New Road ground typifies the quaint pleasantness of the English season. Thousands of wins, draws and losses have played out under the watchful gaze of Worcester Cathedral ever since the first wicket was marked out a short distance from its central tower in 1896. The River Severn trickles along past the eastern edge of the boundary rope as spectators while away the peak summer days of July and August.

It is, in short, a picture book example of the English county cricket season and one that has remained predominantly unchanged for more than a century.

Flooding on South Parade, Worcester - Philip Halling

Flooding on South Parade, Worcester - Philip Halling

New Road Cricket Ground, Worcester - Stephen McKay

New Road Cricket Ground, Worcester - Stephen McKay

An English Tradition

The 39 historic counties of England and Wales (as established by the Normans after their arrival on these shores in 1066) have been competing in cricket matches since 1709.

It was the Victorians and their love of order and control who set about organising the game into the codified sport that we see today. The first season of England’s first-class cricket competition, the County Championship, was played in 1890.

The County Championship is English cricket’s domestic first-class competition and forms the bedrock of competition between 18 of the 39 historic counties of England and Wales (17 English and 1 Welsh).

The 18 First-Class Counties

Worcestershire CCC

- The archetypal English county.

- Based at New Road, Worcester.

- Founded in 1865

- Known to most fans as 'The Pears'

Surrey CCC -

- With annual revenues of £32m, the wealthiest county in England and Wales.

- Play at The Oval in Kennington, South London

- Founded in 1845

- Logo depicts the Prince of Wales' feathers as he owns the land on which The Oval stands.

Sussex CCC

- Founded in 1839, the oldest of the 18 first-class counties.

- Play at the County Ground in Hove.

- The most dominant team in the country during the 2000's as they won ten trophies in ten years.

- Known as 'The Sharks' when competing in limited overs competitions.

Brave New World

Cricket’s close association with the values of Victorian society made it unquestionably the most popular sport in the country at the turn of the 20th Century – it’s most famous protagonist, WG Grace, is considered the first sportsperson in history to attain international acclaim.

But the counties’ slower adoption of modern business practices such as marketing and communications compared to other sports made them particularly vulnerable to changes in consumer habits and tastes.

By the time the IPL was founded in 2008, county cricket was in no state to challenge the glitz and the glamour of its newer, faster rival.

By comparison, the most successful English county, Surrey CCC (founded: 1845), currently has 149k Instagram followers, while the IPL’s Mumbai Indians (founded: 2008) have 11.8 million - nearly 80 times the number.

The ripples of the inaugural IPL auction were even felt as far afield as McLean Park in Napier where all-rounder Dimitri Mascarenhas was midway through England’s limited overs tour of New Zealand, as yet blissfully unaware of the relentless cha-ching of cash registers on India’s west coast.

Mascarenhas was on his way to a training session when his phone began to buzz in his pocket. His county teammate at Hampshire, Shane Warne, had just been bought for $450,000 by the Rajasthan Royals in the auction and was on the lookout for a familiar face to join him on the team.

“It was completely out the blue," Mascarenhas told ESPNCricinfo’s Tom Wigmore. "Warnie said, 'Do you want to come?' I was like, 'Absolutely, yeah.’”

"There was a lot of resistance", Mascarenhas said. At that time, the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) was suspicious of the riches being offered by this new Twenty20 league and believed the IPL did not have the best interests of the sport at heart.

Fortunately for Mascarenhas, Hampshire permitted him to take part, allowing the all-rounder to participate in the IPL with the caveat that he would only play for two weeks of the two-month-long IPL season so as to miss as little of the English county campaign as possible.

"I understood that from Hampshire's point of view, losing their captain from the first two months of the season wasn't great. We came to a compromise which suited both."

"It wasn't ideal”, Mascarenhas recalled. “Warnie wanted me to go for the whole thing. Initially, I wanted to go for the whole thing as well. But I understood that from Hampshire's point of view, losing their captain from the first two months of the season wasn't great. We came to a compromise which suited both."

Mascarenhas subsequently joined Warne at the Rajasthan Royals, pocketing $100,000 in the process.

Dimitri Mascarenhas playing for Hampshire at the County Ground, Hove in May 2009 - Richard Avis

Dimitri Mascarenhas playing for Hampshire at the County Ground, Hove in May 2009 - Richard Avis

Shane Warne bowling for the Rajasthan Royals against Middlesex at Lords in 2009 - Chris Brown

Shane Warne bowling for the Rajasthan Royals against Middlesex at Lords in 2009 - Chris Brown

Hampshire’s reluctance to allow their player to sign for another team abroad was shared by the other 17 counties, while the ECB’s attitude at the time was summed up by former England captain Ray Illingworth who told The Guardian, “I think it would be greedy of them to take the money of the IPL at the expense of their contracts with England and their counties.”

England’s best cricketers were prohibited from participating in the entirety of a single IPL campaign until 2020.

The traditional conservatism of English cricket was suspicious of the IPL’s glitzy bravado, and it had some right to be.

In the years since that ground-breaking first season in 2008, the IPL has enjoyed exponential financial success, driven by the devotion of the country’s cricket-loving population of 1.4 billion people.

The IPL’s broadcast deals are currently worth five times what they were just 15 years ago, in 2008. The league recently agreed a £5bn, five-year broadcast deal that has made it the second most lucrative competition in the world on a per-match basis, above English football’s Premier League and behind only the NFL.

Conversely, English County cricket has decreased in relevance and popularity to the point where the 18 first-class counties rely on the ECB for financial aid to prevent them from going under.

Warning Signs

With financial success comes power and the ability to attract the best players and coaches. As a result, many of the world’s star cricketers choose to play in the IPL over representing their domestic sides as well as their countries.

The two-month long IPL tournament stretches from the end of March to the back end of May. Its influence on the sport reaches so far and wide that the international cricket schedule is now almost totally cleared to avoid any fixtures overlapping with it.

This has had greater significance in England where matches had habitually been played in May.

The English summer and its place within the international cricketing calendar is coming under increasing threat from new Twenty20 franchise leagues that have sprung up in the Dubai, South Africa and the USA, all keen to replicate the IPL’s commercial success.

The English county game is simply unable to financially compete with these rival leagues and, with the best talent understandably following the money, the standard and watchability of pre-existing English competitions suffers as a result.

The County Cricket Ground, Hove - Tom Chambers

The County Cricket Ground, Hove - Tom Chambers

The County Cricket Ground, Hove - Tom Chambers

The County Cricket Ground, Hove - Tom Chambers

Despite its rich sporting and cultural history, domestic English cricket is currently facing the greatest threat to its existence since becoming a codified sport in 1890.

New market forces are placing the counties’ very existence under threat as players, coaches and audiences are attracted to new competitions in other parts of the world.

In recent years, county cricket has experienced unprecedented upheaval as the ECB struggles to generate the financial support that the English game needs to ensure the continuation of its 300-year history.

That hotel basement in Mumbai was contemporary cricket’s ground zero. The rapid modernisation of the world’s oldest professional sport caused shockwaves that are still being felt now, more than 15 years later.

The Counties' Conundrum

Counties are the foundation of the professional game. They identify and develop young cricketing talent, preparing the very best for selection to the England team. If the county game fails, then so too does the very structure of the second most popular professional sport in this country.

County cricket in England and Wales has an accumulated debt of between £180 million and £200 million with many teams relying on ECB funding to continue to operate.

English Cricket still generates the majority of its income from gate receipts and is therefore particularly vulnerable to changes in consumer habits and unforeseen events (such as the Covid-19 pandemic).

Research by Sheffield Hallam University discovered that 59% of county revenue was generated by gate receipts, international gate receipts, hospitality and non-cricket events such as music concerts. By way of comparison, Deloitte’s annual research into elite football clubs (Football Money League) shows that the richest teams generate less than 15 percent of their income on a matchday. Their annual turnovers are far more reliant on broadcast (44%) and commercial (41%) deals.

The post-pandemic 'new normal' of staying at home is also having an effect. Last season’s Vitality Blast Twenty20 campaign saw a 15% decline in attendances compared with pre-pandemic numbers while spectators for County Championship matches are often counted in the hundreds rather than the thousands.

The County Cricket Ground, Hove - Tom Chambers

The County Cricket Ground, Hove - Tom Chambers

Other popular sports and their governing bodies do not place such a reliance on gate receipts because of their lucrative broadcast deals.

The ECB recently extended their broadcast rights deal for county cricket with Sky Sports for £220 million per year, but Richard Thompson, the new ECB chair, has warned the game still faces an uncertain financial future in a time of high inflation and a cost of living crisis.

At the time of writing, two English counties (Yorkshire and Middlesex) are behind on their respective debt repayments and facing a fight for survival.

The delicate financial existence of many counties suffered a near-fatal blow in the Spring of 2020 when the Covid-19 pandemic forced the closure of stadiums across the country, requiring matches to take place behind closed doors.

Sheffield Hallam's research found that the effects of closed stadiums and cancelled competitions left a £120 million hole in county cricket’s finances. Many counties only avoided insolvency thanks to extensive financial support from the ECB.

Fresh Hope?

But it’s not all bad news for the counties. While the pandemic underlined cricket’s reliance on the revenue at the gate, it did provide teams with an opportunity to innovate as they searched for new methods of generating income, the most successful of which has been the adoption of live streaming.

Pre-pandemic coverage of the County Championship was patchy at best, but now all fixtures are available to view online for a small fee or subscription, allowing fans from all over the world to watch contests that otherwise weren’t televised.

The availability and quality of cricket streaming in England and Wales have been steadily increasing since Nottinghamshire pioneered the idea in 2014. But closing stadiums to spectators in 2020 understandably caused a spike in online viewership to the point where more than 700,000 people watched each round of fixtures in the County Championship season.

Viewing figures more than quadrupled, spiking from a baseline of 2000 to more than 8000.

The ECB recognised the value of this digital revolution and now make all enhanced streams available within their app, allowing the sport to generate valuable advertising revenue.

The interest in streaming County Championship matches has even extended overseas. Whenever Sussex CCC’s Indian opening batsman Cheteshwar Pujara is at the crease, viewer numbers increase by thousands.

Cheteshwar Pujara - Naparazzi

Cheteshwar Pujara - Naparazzi

On one occasion last season, with Pujara approaching a century, the viewing figures more than quadrupled, spiking from a baseline of 2000 to more than 8000.

The Hundred - Friend or Foe?

The ECB has continued to innovate as it searches for new ways to grow the county game. In 2021 it launched The Hundred. A controversial new domestic competition that (as well as dispensing with some of the accepted rules of cricket such as six-ball overs), for the first time, did not include the 18 counties.

Instead, The Hundred is played by eight new franchise teams more closely linked to the UK’s major cities (the counties only agreed to The Hundred’s creation after being promised £1.3 million each per year by the ECB).

Many within the game see The Hundred and its franchise system as a means of expediting the slow decline of the 18 first-class counties by rescheduling their fixtures and excluding their involvement.

However, the ECB’s director of men’s cricket Rob Key believes The Hundred will ensure the counties’ future by attracting new fans and generating additional revenue.

"I've always seen The Hundred as the way to sustain the county game."

In an interview with his former England teammate Mark Butcher in Wisden Cricket Monthly Key said, “We’ve added a month to the season with The Hundred and now we’ve got to find space. For me I would end up playing less four-day [County Championship] cricket, because that’s the biggest chunk of the summer. I know everyone will start nailing me for that but financially, the county game, like the rest of the country, is not in the world’s greatest shape. And I’ve always seen The Hundred as the way to sustain the county game."

"You need all these counties as hubs for players to come through, giving people a love for the game. You need to have the best possible standard you can, the best players playing against each other”, Key continued. “You’d be taking two Championship matches away from a home venue, and that’s the trade-off."

"I want my kids’ kids to be able to go and watch the cricket in these places in 20 years’ time, and we have to move with the times because the model has just changed overnight with all this cricket. But I completely accept and understand that there are not many county supporters who want to see that.”

2023 English County Cricket Fixture Calendar

One of the biggest hurdles that counties face while attracting fans is the scheduling of competitions.

The peak summer month of August and its position within the school holidays is dominated by The Hundred competition and its city-based franchises, while the County Championship has been shunted to the peripheries of the domestic calendar in April and September.

Limited overs fixtures in the Vitality Blast and One Day Cup also frequently take place on midweek evenings when school and work commitments often take priority for would-be spectators.

Cricket's Elitism Problem

Final Reckoning

While county cricket is currently facing up to a number of forces seeking to challenge its very existence, it is important to note how resilient it has been.

Many consider it to be a quirk of the English psyche to be able to find catastrophe where there is none. County cricket has been considered to be ‘in crisis’ for much of the past one hundred years. The counties have proved to be remarkably resilient throughout their existence, surviving two world wars and two global pandemics along the way.

That being said, the county game has never been as weak as it is now.

Many of its symptoms have been self-inflicted as mismanagement and repeated failures at modernisation have seen it atrophy while its competitors have built strength. The financial problems that came with the pandemic have accelerated these difficulties and especially highlighted the offering of the county game for a TV-watching public. The growing omnipotence of the IPL and its franchise-based imitations have forced the county game to retreat to the last vestiges of the calendar.

County cricket has survived against the odds before but now it must do so again.

Sussex CCC: A Case Study In The Problems Of The County Game

Words - Daniel Bentley

Trouble on the South Coast

Sussex County Cricket Club is the oldest of the 18 first-class counties within the domestic cricket structure of England and Wales.

Traditionally a bastion of the county game, it has now prioritised the new formats in cricket and the money that comes with them.

In recent history, the county – playing as the Sussex Sharks – have been dominant in white ball cricket and have concentrated on the Twenty20 format for several years.

Short-term Pain

Sussex have said they will be using their youth setup for players for the County Championship – and by doing that have in effect written-off short-term chances of promotion.

This might be presented as a rebuilding exercise, but it cannot be argued that this is organic. Instead it is based on shifting resources away from the red-ball game and instead focusing on the white-ball game, which is bringing in more revenue.

Long-term Gain

That said, Sussex are now seeing some youth players like Ollie Robinson, Tymal Mills and Jofra Archer go on to play for England in different forms of the game, whether it be in Twenty20 or Test Match cricket.

Young players given responsibility are beginning to take up the slack created by less spending on established talent.

Sussex have, however, found the money to sign star players on white-ball-only contracts – done because these players want to avoid injury playing in all formats.

These star plays attract more spectators, viewers and money giving even more incentive to spend on the white ball game.

The County Cricket Ground, Hove - Tom Chambers

The County Cricket Ground, Hove - Tom Chambers

Tymal Mills - Tom Chambers

Tymal Mills - Tom Chambers

Declining Support

Despite a proud history in first-class cricket since the County Championship first started in 1890, Sussex now finds itself struggling in the second division.

From 2000 to 2010 the side won three County Championships with back-to-back first-division titles in 2006 and 2007. But in 2015, they were relegated to the second division.

There are now around 1,600 members at Hove, the lowest count in living memory

The continual losses and lack of competitiveness at the championship level seem to have led to a decline in Sussex’s membership, as members do not want to sign-up to watch a package of County Championship games in which they are not competitive.

There are now around 1,600 members at Hove, the lowest count in living memory and around a third of the total from 2007.

As well as falling membership, existing members have complained, and many red-ball players have moved on to other counties.

On social media, members even mocked an initiative to get them to sign up for five-, ten-, or fifteen-year packages – marketed under the slogan: “Marching to Our Future.”

This was launched just as the club had been thrashed by an inning at the hands of Durham and finished 17th out of 18 in the County Championship after recording just one win in 14 matches, and had just three wins in three years, a quite staggering stat.

Members rightly questioned what the state and worth of their club’s county game would be in even a few years’ time.

The County Cricket Ground, Hove - Tom Chambers

The County Cricket Ground, Hove - Tom Chambers

Star Power

Despite Sussex dropping down a division and not playing to the heights of earlier years, the club are still able to pull in high-calibre players and may now even be putting something back into the red-ball game.

For example, Steve Smith, former Australia captain and a household name in test match cricket, signed for Sussex in January 2023 – although this was on a short-term contract.

Steve Smith - Naparazzi

Steve Smith - Naparazzi

This will certainly bring quality and leadership to the team, as Sussex look to bounce back to the first division in the County Championship.

The county will be itching to get back to where they once were in the first division – even if this is simply for prestige. With the County Championship season underway on the 6th April, they will hope the likes of Steve Smith and Indian opening batsman Cheteshwar Pujara, assisted by Sussex's home-grown youngsters, can get the county back to winning ways.